Capitalism vs Climate Crisis:

Why It’s Time For Capitalism To Die Before We Do

Doubtless there will be some people who read that headline and immediately dismiss the rest of this article as pro-communist, hippy rubbish.

This is a common issue that we face – the idea of binaries. That to be anti-capitalist is to be communist, but there are other alternatives and this article seeks to set out specifically why the model of capitalism isn’t compatible with fighting the Climate Crisis.

Consumption & Combustion

The core tenets of capitalism are consumption and profit. It is essential for a corporation to consistently increase the former in order to increase the latter – and the value of companies on stock markets is tracked by how long they can sustain this growth, rather than the assets that they hold.

However, it has been clear for at least three decades that increased consumption is driving the Climate Crisis, and that averting the worst outcomes of the Climate Emergency – which include the deaths of millions, the displacement of billions, and increased extreme weather events, including famines – will require a swift reduction in both consumption and emissions.

Yet history has taught us that the capitalist system is inherently adverse to this approach – and actively promotes both increased consumption and emissions.

Lessons From History

We are all aware of just how poor capitalism’s ecological record is, whether we realise it or not.

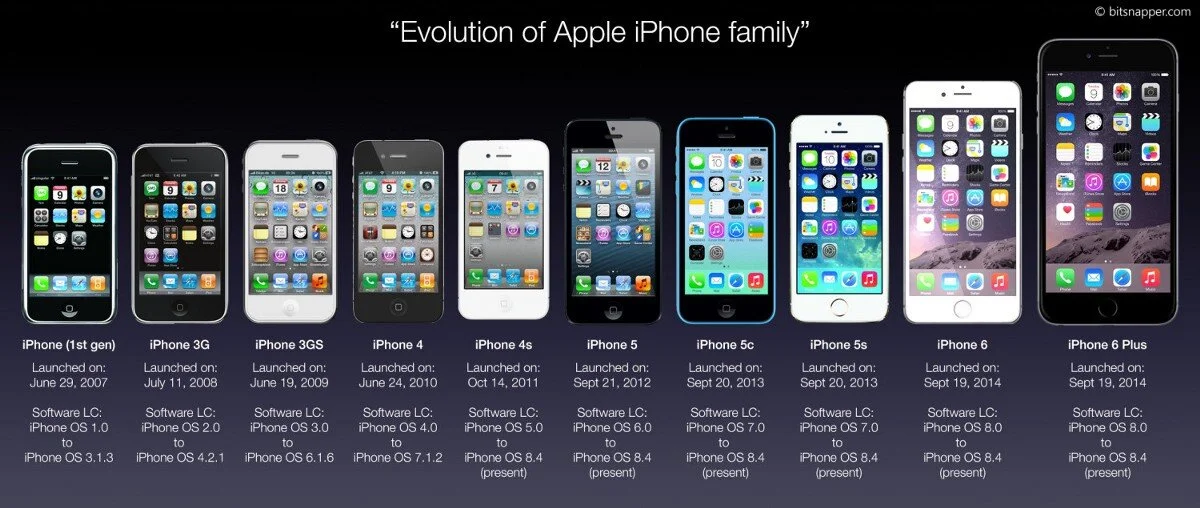

In recent years we have witness multiple lawsuits against Apple alone for the planned obsolescence that it designs into its iPhones, making them harder to fix and deliberately slow down after just a few years so that consumers buy a new one.

These deliberate design choices have resulted in an average life expectancy of just 2.5 years for smartphones in Europe, meaning that the average person will get through around 35 smartphones in their lifetime.

This has resulted in 49.8 million tonnes of e-waste since 2018 alone.

Yet the idea of planned obsolescence has been around a lot longer than you probably realise.

It’s roots can be traced back to the 1920s and the light bulb industry.

Miniscule aesthetic changes on a regular basis are a key part of planned obsolescence. Apple’s regular production of minor upgrades is a key example of this, especially when they include design changes that require the use of new peripherals. Credit: Bitsnapper

By the early 1900s, the process for making light bulbs had been refined to such an extent that they could be used almost indefinitely – as seen through the Centennial Light, which has been lit continuously since 1901.

Yet, the improvements failure rate posed a problem – people simply didn’t need to buy as many, and the marketplace was exponentially dwindling.

As a result, the world’s biggest light bulb manufacturers convened a meeting in Switzerland to agree on artificially reducing a bulb’s lifespan to no more than 1,000 hours. They even implemented tests to fine any manufacturers who produced products that lasted longer than this imposed restriction – and so in-built obsolescence was born.

As with all things that are ecologically harmful, it wasn’t long before the car industry started to implement this approach.

In the mid-1920s, GM CEO Alfred Sloan took the idea of planned obsolescence and elevated it to new heights. Every year his company would release updated models in new colours that would only be available for a short period of time or with updated looks.

While Henry Ford declared in 1922 that: “We never make an improvement that renders any previous model obsolete,” this was a dying approach, and in 1955, GM’s Head of Design, Harley Earl, stated: “Our big job is to hasten obsolescence. In 1934 the average car ownership span was 5 years, now it is 2 years. When it is 1 year, we will have a perfect score.”

This approach really took off in the 1950s with the explosion in the advertising and marketing industries, where the idea of planned obsolescence was replaced by dynamic obsolescence – where the redesign of goods or services is intended to render existing products out-dated and obsolete. This can be best summed up by Brooks Stevens’ phase “Instil in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary.”

This is still the predominant force in consumerism today: limited edition rose gold iPhone anyone?

Of course there are instances where a product justifies being replaced due to technological advances; for example, when a more efficient and lower emission engine becomes available for the first time.

But these innovations are rare and aren’t what drives capitalism or consumerism today.

We know this to be true. We only need to remember how long phone batteries used to last a decade ago to see that upgrading to a smartphone that has more rounded corners or slightly a better camera, but which requires peripheral products to allow us to continue using headphones, isn’t progress.

This is capitalism in action.

This is also the Climate Crisis in action, as this approach breeds the continued consumption of our planet’s finite resources. A case in point is that just 5% of the lithium-ion batteries used in the 1.5 billion new smartphones sold each year currently go on to be recycled.

This needs to stop, and part of the responsibility lies with us to stop buying into this capitalist conditioning.

NFTs

While NFTs warrant a whole article of their own, we could perhaps see these as the embodiment of how harmful late-stage capitalism has become in recent years.

People are spending millions of dollars on essentially nothing. A digital token for something that either physically exists elsewhere, or which is already widely available in the digital world – such as gifs.

NFTs have no value other than being exclusive and for the new ‘owner’ being able to say that they possess them. Worse still, NFTs are creating vast new emissions that didn’t exist previously, just so that people individuals can make a profit.

We say individuals, but brands from Coca Cola to Funko, and Pringles to Formula 1 are selling NFTs for profit.

NFTs consume vast amounts of energy, and create huge amounts of heat waste. One analysis shows that a single NFT can use the same amount of energy that the average EU resident uses in a month. Credit: Memo Akten.

The process of storing and selling NFTs is wholly inefficient, requiring vast amounts of energy and producing huge heat losses.

A recent analysis found that the sales of one artists’ NFTs over half a year resulted in the equivalent electricity consumption of the average EU citizen over 77 years, or driving a petrol car for 838,000 km.

Remember that these emissions simply did not exist a few years ago – and that the idea of ‘offsetting’ these by planting trees is little more than greenwashing lies.

Rise of Greenwashing

In recent years we have seen corporations evolve as consumers have increasingly demanded action to reduce emissions and increase the sustainability of the products that they consume.

However, rather than taking steps to reduce the ecological and climate impact of their products, we have seen corporation after corporation engage in greenwashing – the act of marketing itself to be ‘green’ while doing nothing to make a meaningful impact on emissions in order to maintain, or even grow, profits.

While big-name brands and governments will constantly spout the phrase ‘green growth’ – there simply is no such thing. We cannot continue along the same path that has caused so much destruction and inequality but under a rebranded name.

As George Monbiot put it in a recent Guardian article: “The categories the human brain creates to make sense of its surroundings are not, as Immanuel Kant observed, the “thing-in-itself”. They describe artefacts of our perceptions rather than the world.”

“Nature recognises no such divisions. As Earth systems are assaulted by everything at once, each source of stress compounds the others.”

“We have no hope of emerging from this full-spectrum crisis unless we dramatically reduce economic activity. Wealth must be distributed – a constrained world cannot afford the rich – but it must also be reduced. Sustaining our life-support systems means doing less of almost everything. But this notion – that should be central to a new, environmental ethics – is secular blasphemy.”

Another Way

Hopefully the above has made it clear that capitalism simply isn’t compatible with overcoming the Climate Crisis, and that it is directly responsible for it in large part.

Turning ours back on capitalism does not mean that we will experience a lower quality of life – far from it.

We see the ills of late-stage capitalism on a daily basis: Amazon workers who have their toilet breaks tracked, or who were forced to work around a colleague who had died; taxpayers forced to bail out banks who then pay their senior management extortionate bonuses equivalent to the bailout; and the discussion of legislation like CETA, which would allow corporations to sue governments that forced them to act ethically.

To be anti-capitalist is not to be communist. It is to see that the prevailing system in the world today only seeks to empower and enrich the few, at the cost of the average person, global ecology and the Climate Crisis.

While we at IrishEVs do not have the answer for what comes next, it is pretty evident that capitalism only works for a select few while subjugating the majority.

What comes next must be a just transition, where we value bottom-up investment, where we value ‘resources’ in their natural state rather than only seeing their monetary value once extracted from the Earth, and where we understand that destroying the life support systems on this planet is not something worth profiting from.

We have less than a decade to avert the worst outcomes of the Climate Crisis, and the mitigation plans put forward by those invested in capitalism just won’t cut it.

What To Read Next

Cost vs Value - The Need To Look Beyond Finances In The Face Of The Climate Crisis

We look at the importance of understanding the difference between cost and value, and why this is a critical distinction in the face of the Climate Crisis

The Plastic Problem & The Climate Crisis

We look at the issue of plastic pollution, and why this matters if we are to avert the worst possible outcomes of the Climate Crisis before it’s too late